The Marmaduke Maids

Mapping Women’s Participation in Colonizing Virginia, 1621

“…fitt hundreth that might be sent of women, maids young and uncorrupt to makes wives to the inhabitants.”

- Sir Edwin Sandys, Virginia Company of London Treasurer, November 3, 1619

Setting The Price of a Bride

In 1619, Sir Edwin Sandys stated to a meeting of the Virginia Company of London that the company would need to start sending marriage-eligible women to their budding settlement on the banks of the James River in Virginia. The men that built and were sustaining Jamestown through planting and selling tobacco needed to start planting family roots in the region as well if they were to continue making the money and pursuing the imperial goals of the British empire. The company needed to appease their settlers who were unhappy with the current conditions, but they were also facing new financial problems after the lotteries that they had been depending upon were ended in a March, 8 1620 royal charter.

The young women were to be sponsored by individuals or the company itself, including expenses for their travel, some comforts aboard the ship, and clothing for the journey. Members of the company would front the cost of their travels and be 150 best leaves of tobacco by the planter upon the impending marriage.

But what of choice? The company was clear that the women must be allowed freedom in their choice of who to marry. And if their intended were not be able to pay the company’s set price, the planter would be asked to pay as soon as possible, placing their debt to the company over any others.

In a letter to the Governor and Council in Virginia in 1621, the company made it clear that they expected the colony to take care of the women once they arrived. Marking a clear line of when the company’s care of the women ended but also not providing distinct directions for the colony paints a picture of an uncertain world for the twelve women in Virginia. How were they to meet a husband? What would happen to them if they did not marry?

A Call for Adventurers

The women that were recruited for the company’s ‘brides for Virginia’ scheme came from a variety of backgrounds, but generally had some tie to the Virginia Company of London. The fourteen women who were recruited to emigrate on the Marmaduke in August of 1621 ranged from ages 15 to 28 and came from fathers who were gentlemen or artisans. They came from an array of home towns but a majority had relocated to London by the time of their recruitment.

On the list of women intended for the Marmaduke, transcriber Nicholas Ferrar also includes the women’s skills that might make them more eligible as a wife to an ancient planter in Virginia. The women’s connections to the company are also listed with anyone who may be recommending them for the journey. This again varies as some women are recommended by employers they are in service to and others by uncles who are knights. How would these connections and skills help them in their new lives in Virginia?

Maids to be Made Wives

This project follows the journeys of the fourteen women listed by Nicholas Ferrar: Lettice King, Allice Burges, Catherine Finch, Margaret Bordman, Ann Tanner, Mary Ghibbs, Jane Dier, Ann Harmer, Susan Binx, Audry Hoare, Ann Jackson, Ann Buergen, Ursula Clawson, and Joanne Fletcher.

In mapping the home towns, last residences in England, and documented settled locations in Virginia, the lives of the fourteen individuals gain definition in the history of England’s Virginia colony. Putting the information we have from the Ferrar Papers collection, Records of the Virginia Company of London, and the 1624/25 Jamestown muster into the women’s geographical context puts their stories into distinct perspective. Women trained in fine embroidery with connections to gentry were to be starting new lives in burgeoning and sometimes struggling plantations like Martin’s Hundred or Flowerdew Hundred. In geographical context we are able to ask how the women may have made connections aboard the Marmaduke on their months long journey across the Atlantic and how those connections or skills may have led them to where they ended up in Virginia. In mapping the journeys of these ‘adventurers’, these early modern women are treated as individuals and their agency in their choice to start new lives can be seen.

While this project was able to pull from a rich well of primary sources for the women’s origins in England, the women’s futures in Virginia are deciphered from the Jamestown muster records where the commonality of early modern English names makes it difficult to definitively connect an Ann from the Marmaduke to an Ann in Flowerdew Hundred. Additionally, only weeks after the Marmaduke’s arrival in Jamestown, the colony was attacked in the early morning hours of March 22, 1622 by the Powhatan Confederacy leading to the death of 350 settlers. The English had been increasingly encroaching on Tsenacommacah, appropriating native land and resources as they stretched their imperial reaches, and Opechancanough combatted the colonizing force with the so-called massacre. Since the musters did not begin until two years after the violence, there is a possibility that some of the women may have been killed. In these cases, or those whose locations are unable to be estimated, the geographical context gives us a sense of where these women may have dispersed.

While acknowledging and highlighting the agency these women displayed in choosing to start new lives in Virginia for a variety of reasons, whether it was hoping for a more stable life or the adventure of seeking new terrain, it is important to also highlight their ability to have a choice at all. The women who were recruited by the Virginia Company were white English women from fairly good means, thus in the 17th century they are juxtaposed by those in 1619 and beyond were shipped to the English colonies in violent coercion. Their agency over the direction of their lives also points to the roles they played in the colonization and violent appropriation of indigenous land.

This project aims to highlight the role women played in the colonization of Virginia in the early seventeenth century by participating in the gendered roles assigned to them in British society of the time. The geographical context of the Marmaduke maids provides a visual that showcases them as individuals who may or may not have had autonomy over their lives and taken a risk in starting new futures in Virginia. With the context of the information each of them provided to the Virginia Company of London and the skills they were bringing to a newly established settlement on the banks of the James River, we can make get a better sense of how much each of their lives must have changed and how much they were really prepared for such a change. Did the women who married the coveted ancient planters regret their decisions to move to the colony? Did the women who did not marry enjoy the change in lifestyle they found in Virginia over the bustle of London?

-

Ann Jackson

Traveled with her brother and his wife to Martin’s Hundred where she was taken prisoner in the so-called massacre of 1622.

-

Audry Hoare

Married ancient planter, Thomas Harris. She is listed in the Jamestown muster of 1624 living at Neck of the Land, Charles City.

-

Catherine Finch

Married an ancient planter, Robert Fisher. She is listed in the Jamestown muster of 1624, living at Jordan’s Journey with a one year old daughter, Sisly.

-

Joanne Fletcher

The eldest of the women at 28, the widow decided against traveling to Jamestown at the Isle of Wight and was replaced by Ann Buergen.

Using the Map

-

Expand the layer options menu in the top right corner by clicking on the layers button. Explore the layers that display the hometowns, last residences in England, and settled locations of each of the women using the color coded key. Be sure to move the map to follow the women to Virginia!

-

Click on the color coded icons on the map to read more information about each of the women.

You will notice that the amount of information on each woman is not consistent and that is due to the primary source material this project pulls from. All available information on each woman has been displayed.

-

Filter the women by age, parental status, and paternal occupation by navigating the filter options on the far right of the page. Be sure to click clear once you are done to return to the base information.

Sources

Cook, Henry Lowell. “Maids for Wives.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 50, no. 4 (1942): 300–320.

FP 280. The Ferrar Papers, 1590-1790, Magdalene College, Cambridge. Virginia Company Archives.

FP 303. The Ferrar Papers, 1590-1790, Magdalene College, Cambridge. Virginia Company Archives.

FP 306. The Ferrar Papers, 1590-1790, Magdalene College, Cambridge. Virginia Company Archives.

FP 308. The Ferrar Papers, 1590-1790, Magdalene College, Cambridge. Virginia Company Archives.

FP 309. The Ferrar Papers, 1590-1790, Magdalene College, Cambridge. Virginia Company Archives.

FP 328. The Ferrar Papers, 1590-1790, Magdalene College, Cambridge. Virginia Company Archives.

Hall, Thomas, and Joseph Luter. 2009. “‘THE DUAL NATURES of ACTIVISM and of the STATE: THE VIRGINIA COMPANY of LONDON, 1606 -1624’ the DUAL NATURES of ACTIVISM and of the STATE: THE VIRGINIA COMPANY of LONDON, 1606 -1624.” https://cnu.edu/publichistorycenter/_pdf/cnu-virginia_company.pdf.

Mohlmann, Nicholas K. "Making a Massacre: The 1622 Virginia "Massacre," Violence, and the Virginia Company of London's Corporate Speech." Early American Studies 19, no. 3 (Summer, 2021): 419-456. http://mutex.gmu.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/making-massacre-1622-virginia-violence-company/docview/2552131376/se-2.

Potter, Jennifer. The Jamestown Brides : The Story of England’s “Maids for Virginia.” New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Ransome, David R. “‘Shipt for Virginia’: The Beginnings in 1619-1622 of the Great Migration to the Chesapeake.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 103, no. 4 (1995): 443–458.

Ransome, David R. “Wives for Virginia, 1621.” The William and Mary quarterly 48, no. 1 (1991): 3–18.

Shifflett, Crandall. Jamestown 1624/5 Muster Databases, 1999. http://www.virtualjamestown.org/Muster/introduction.html.

Vaughan, Alden T. “‘Expulsion of the Salvages’: English Policy and the Virginia Massacre of 1622.” The William and Mary quarterly 35, no. 1 (1978): 57–84.

Virginia Company Of London, Library Of Congress, and Woodrow Wilson Collection. The records of the Virginia Company of London. editeds by Kingsbury, Susan M Washington: Govt. Print. Off., to 1935, 1906. Image. https://www.loc.gov/item/06035006/.

Images

Fig 1: John Clark Ridpath, “Wives for the Settlers of Jamestown” in United States; a history: the most complete and most popular history of the United States of America from the aboriginal times to the present day…, 1893. Library of Congress.

Fig 2: Velde, Willem van de. “Drawing”. Drawing in chalk, with grey wash over graphite on paper. Depicting the arrival of Charles II at Gravesend on the Thames. Prints and Drawing Department: The British Museum, 1611.

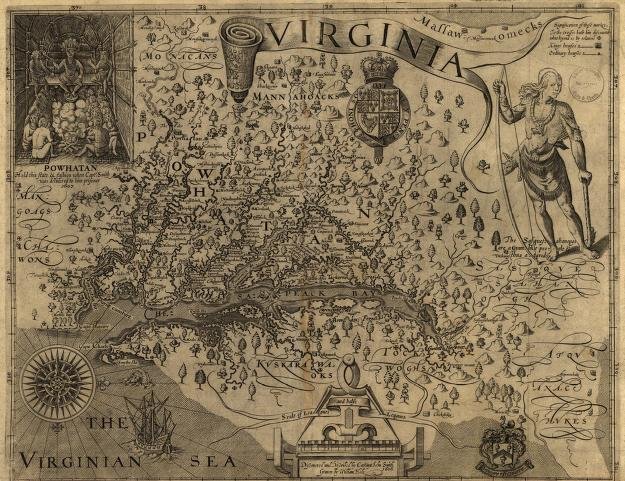

Fig 3: Smith, John, and William Hole. Virginia. [London, 1624] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/99446115/.